In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

Harry Harrison’s Deathworld, despite it being his first novel-length work, turned out to be one heck of a good read, and a book that has held up well over time. It is a perfect example of the house style John Campbell demanded of Astounding/Analog writers, but at the same time has all the hallmarks that run through Harrison’s work: a self-reliant protagonist, authorities who need a comeuppance, and a deep distrust in violence as a solution to problems. The planet that gives the book its title is a nifty piece of world-building, and there is a strong ecological message that runs throughout. And while the book is full of action and adventure, it ends up advocating a remarkably peaceful solution

When I found this paperback edition of Deathworld in a used bookstore a few months ago, I thought I was in for a re-read, but was surprised to find, while I had read the sequels, the book was new to me. When I was young, I often picked up Analog and read stories at random, and even jumped in in the middle of serialized novels. Analog made that easy to do by providing a synopsis of what had gone before at the beginning of each installment. Even after all these years, it was a pleasure to discover that I had finally found the start of the Deathworld series.

I also had the vague impression the Deathworld novels were the first adventures of the character known as the Stainless Steel Rat, or James Bolivar DiGriz. But it turns out the main character of Deathworld, Jason dinAlt, is a different person altogether. Others have commented on similarities between the two characters, so it’s not surprising my memory conflated them. And I suppose I can blame some of the fuzziness of my memory on the fact it was about fifty years ago I encountered the stories.

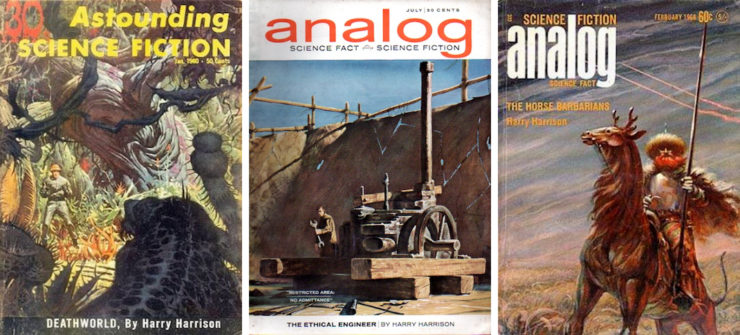

Deathworld was serialized starting in January 1960, which was the last issue of the magazine that had only the name Astounding on its cover (for a time, Astounding appeared alongside Analog on the cover, until the former name eventually disappeared altogether). The story was popular enough that a sequel, The Ethical Engineer, was serialized starting in July 1963. And in February 1968, a third novel, The Horse Barbarians began its serialization. When the novel versions appeared, they were much more simply titled, with Deathworld being followed by Deathworld 2 and Deathworld 3.

Harrison closely follows Campbell’s house style in many aspects of the tale. His protagonist has extrasensory or “psi” powers, and is a competent, action-oriented hero who excels at solving problems. But you can also see Harrison’s anti-war attitudes coming through as the story progresses. To survive, the inhabitants of Deathworld must learn not to kill their enemies, but make peace with them.

About the Author

Harry Harrison was a popular science fiction author for many decades after his career began in the 1950s. He got his start in the comic book industry as an illustrator and writer, and for a time, scripted the Flash Gordon newspaper scripts. He was one of the stable of writers who contributed to John Campbell’s Astounding/Analog Science Fiction magazine, but eventually grew weary of Campbell’s heavy-handed editorial policies, and branched out to other magazines, including Fantasy and Science Fiction, If and Vertex. Among his most popular works was the often-humorous series of tales that followed the career of con man James Bolivar DiGriz, known as “The Stainless Steel Rat,” and mixed satire with adventure. He wrote many works in a variety of sub-genres, including humor and alternate history, and also more serious books like Make Room! Make Room!, which was later adapted into the movie Soylent Green.

Harrison was liberal in his politics, anti-war, and distrustful of bureaucracies and authority in general. His classic satire Bill, The Galactic Hero (which I reviewed here), was written in response to Robert Heinlein’s jingoistic Starship Troopers. And in 1991, with Bruce McAllister, he edited the anthology There Won’t Be War, which included stories from Isaac Asimov, William Tenn, Kim Stanley Robinson, James Morrow and others, an anthology which was intended to provide an alternative viewpoint to Jerry Pournelle’s pugnaciously titled There Will Be War anthology series.

Harrison did not have any individual works that won either the Hugo or Nebula Awards, but because of his overall body of work and contribution to the field, he was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2004 and was named as a SFWA Grand Master in 2008.

As with many authors who were writing in the early 20th Century, a number of works by Harrison can be found on Project Gutenberg, including Deathworld.

The Art of Astounding/Analog Science Fiction

As a young reader, one of my favorite part of reading my father’s science fiction magazines was seeing the artwork. I enjoyed having an image of the characters, the settings, and the technology portrayed in the stories. I have read that John Campbell had a role in changing the artistic approach for the magazine, replacing the lurid covers of the pulp era with much more respectable illustrations, something an aerospace engineer like my father could read during his lunch hour without embarrassment. And the interior black and white illustrations were as good as the covers. The Deathworld trilogy provides a good cross-section of that work, having been illustrated by three of Analog’s best artists.

The first installment of Deathworld had a cover by Henry Richard (H. R.) Van Dongen (1920-2010). His figures were often angular and stylized, but rich with fascinating detail. His association with Astounding ended during the 1960s, just as I was starting to read the magazine, so I didn’t see much of his work until his return to science fiction illustration later in his career. Many of his works can be seen on Project Gutenberg.

The cover for first installment of The Ethical Engineer was painted by John Schoenherr (1935-2010), who had a very distinctive style, and was a noted illustrator in both the science fiction community and beyond. His illustrations were often loose and impressionistic, and his imaginings of alien creatures were very evocative. One of his most famous cover illustrations was for Dune by Frank Herbert. His awards included a Best Artist Hugo, a Caldecott Medal and induction into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame. You can see examples of his illustrations on Project Gutenberg.

The final novel of the trilogy, The Horse Barbarians, appeared in an issue with a cover by Frank Kelly Freas (1922-2005), in my humble opinion, the best Analog artist of all time. One of my favorites is the cover of Astounding for “The Pirates of Ersatz,” by Murray Leinster. He had a very bold, colorful and often humorous style that appealed to my young eyes, and still pleases me today. One of my most valued possessions is an original interior pen and ink illustration he did for The Horse Barbarians. Freas garnered nine Best Artist Hugo Awards and two special Hugos, was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame, received a wide range of other awards, and is sometimes referred to as “The Dean of Science Fiction Artists.” You can see his cover work accompanying numerous entries on Project Gutenberg.

Deathworld

Jason dinAlt, a professional gambler, has a request to meet a man named Kerk Pyrrus. Pyrrus reminds Jason of a retired wrestler, and wears a gun in a sleeve holster. Jason is suspicious, as his profession can often lead to trouble, but Kerk wants to hire him. He has a stake of 27 million credits that he wants to run up to a billion. Jason has psi powers that he can use to influence the dice, and Kerk seems to know that. The job will be dangerous, as no casino wants to lose that much money, especially the corrupt casino they have selected. Jason wins three billion, but the casino isn’t content with the results, and the two must battle their way off the planet.

Kerk is from the planet Pyrrus, an intensely volcanic, heavy two-G world with extremely volatile weather systems, which is also rich with heavy and radioactive elements. And these intense conditions have caused an ecology to evolve that is aggressively hostile to the human colonists. The money will go to buy the military weapons and materials the colonists need to survive. Jason, even though his cut gives him enough money to retire comfortably, is bored with his life, and insists that Kerk take him to Pyrrus so he can see this planet for himself.

The two men travel to a world where they can buy their materials, and board a Pyrran space vessel for the return home. The ship is piloted by a beautiful young Pyrran woman named Meta, who Jason falls for, and they begin an affair. Meta is notable for stories from that era, as she more than just a love interest; she is every bit the equal of the men in the tale, and has plenty of agency. While the story hints at the equality women have on Pyrrus, the story would have been improved by showing us more female characters. Everyone he meets treats Jason like he has signed his death warrant, and when he arrives on Pyrrus, he is thrown into training classes with children, and treated like a child. And on Pyrrus, that means he trains to kill, without hesitation, anything that is the least bit threatening. The gravity and weather are bad enough by themselves, but the animals and even plant life on the planet is constantly threatening the colonists with gruesome death. Jason is surprised when Meta dumps him, an indication of the unsentimental attitude the colonists have adopted in their efforts to survive. Harrison does a marvelous job describing the colonists, their attitudes, and the harsh conditions and dangers they face.

Jason finally gets permission to go outside, and has some exciting encounters with the vicious creatures he finds. He sees signs that the colony is not thriving, and decides to investigate their history, something the Pyrrans have not done. He hears a reference to “grubbers,” despised humans who live outside the colony. Despite being warned away, he decides to meet them, and finds something strange. There are people living fairly peaceful lives outside the colony despite the harsh conditions. Without going into details, Jason finds there are strange conditions and organisms in the local ecology that make the planet truly unique, and discovers that the colonists might be their own worst enemies. Revealing those mysteries, and how Jason brings the colonists to face their situation constructively, would spoil a big part of the book’s appeal, so I will leave my recap here.

Final Thoughts

Harry Harrison was a marvelous author, often thought-provoking, and always entertaining. While I just read Deathworld for the first time, it immediately ranked among my favorites of his many works. Like all books of its era, there are elements that date it. But it hangs together quite well, the central mystery is fascinating, and the resolution is very satisfying. And, since it is available for free on-line, there’s no reason not to hunt it down and dig in.

And now I’m finished talking, and it’s your turn to chime in. What are your thoughts on Deathworld and its sequels? Are they your favorite works by Harry Harrison, or are there others you like better? I always enjoy seeing what other people have to say, so don’t be shy about joining the conversation.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.